Half a century after Concorde first roared into commercial service, the world is once again looking skyward.

The 50th anniversary of that inaugural 1976 flight is more than a milestone in aviation history it’s a reminder of a time when travel felt impossibly glamorous, defiantly futuristic, and proudly Anglo‑French. Concorde wasn’t just an aircraft; it was a cultural moment, a technological leap, and for those lucky enough to step aboard, an experience that stayed with them for life.

One of those passengers is Norma Millington, who still speaks about her 1992 Concorde journey with the kind of awe usually reserved for first loves or once‑in‑a‑lifetime adventures. In April of that year, she boarded the supersonic icon for a flight to Toronto part of an extraordinary multi‑leg trip that also included the Orient Express and the QE2. “It was an amazing experience and an amazing plane for that time,” she recalls. “You just knew you were part of something special.”

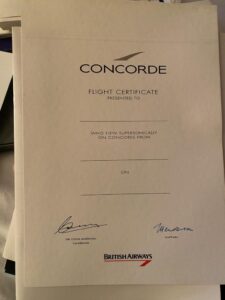

Her ticket cost £485, a price that would equate to well over £1,000 today astonishingly modest for a seat on the world’s most exclusive commercial aircraft and Norma kept everything: the menus, the boarding passes, even her certificate confirming she had flown supersonic, signed by British Airways chairman Sir Colin Marshall and Captain Henderson. These mementos now read like artefacts from a vanished age of travel.

The menu alone is a snapshot of early‑90s luxury, albeit with a few quirks by modern standards. Champagne – naturally – flowed freely. Passengers were served a fruit appetiser followed by a cold collation of fillet of beef and grilled chicken with potato salad, cherry tomatoes and a forestière garnish. Then came Stilton with crackers and a selection of fine chocolates. “It sounds odd when I read it back,” Norma laughs, “but for the era it was very upmarket.” and at Mach 2, even Stilton tasted better.

The menu alone is a snapshot of early‑90s luxury, albeit with a few quirks by modern standards. Champagne – naturally – flowed freely. Passengers were served a fruit appetiser followed by a cold collation of fillet of beef and grilled chicken with potato salad, cherry tomatoes and a forestière garnish. Then came Stilton with crackers and a selection of fine chocolates. “It sounds odd when I read it back,” Norma laughs, “but for the era it was very upmarket.” and at Mach 2, even Stilton tasted better.

What she remembers most vividly, though, is the sensation of speed. Concorde’s cabin was famously compact, and Norma admits the seats “weren’t that comfortable.” But comfort was never the point. The point was 3 hours and 45 minutes across the Atlantic — a journey so fast you could watch the curvature of the Earth through the window while your glass of champagne barely rippled.

Concorde’s retirement in 2003 remains one of aviation’s most emotional farewells. Norma was there for the final day of flights, watching as the aircraft returned home to crowds of spectators, fire trucks creating ceremonial water‑cannon salutes, and a sense of collective disbelief that this chapter was closing. “They taxied around the runway for the last time,” she says. “Everyone was cheering, waving, crying. It felt like saying goodbye to a friend.”

Today, Concorde lives on, not in the sky, but in museums and heritage centres across the UK, France, and the US. Each aircraft has become a pilgrimage site for aviation fans: Alpha Foxtrot at Aerospace Bristol, the last Concorde ever built; G‑BOAB resting at Heathrow; G‑BOAC at Manchester; and others preserved in New York, Seattle, and Paris. Visitors still step inside, sit in the narrow seats, and imagine what it must have felt like to outrun the sun.

Today, Concorde lives on, not in the sky, but in museums and heritage centres across the UK, France, and the US. Each aircraft has become a pilgrimage site for aviation fans: Alpha Foxtrot at Aerospace Bristol, the last Concorde ever built; G‑BOAB resting at Heathrow; G‑BOAC at Manchester; and others preserved in New York, Seattle, and Paris. Visitors still step inside, sit in the narrow seats, and imagine what it must have felt like to outrun the sun.

On it’s 50th anniversary, Concorde’s legacy feels more poignant than ever. In an age of delayed flights and shrinking legroom, the idea that passengers once crossed the Atlantic faster than the rotation of the Earth feels almost mythical. Yet for people like Norma Millington, it wasn’t a myth it was a moment in time, sealed in memory, ticket stubs, and a certificate signed by the men who made supersonic travel possible.

Concorde may never fly again, but its story and the stories of those who flew on it remain timeless.